Women’s health statistics provide important information about the risk of disease within the population. These statistics also show that some populations are at greater risk of health problems than others.

One key area of study is health problems in communities of color. One population that may be at particularly high risk is African American women.

Below, find heart disease in Black women statistics. These data indicate just how essential it is to take steps to reduce heart disease risk factors in this population.

Key Heart Disease In Black Women Fact

Heart disease affects 47.3%[1] of Black women.

Black women had 2.4[2] times the risk of developing heart disease than White women.

Black women are 50%[3] more likely to have high blood pressure as compared to White women.

IAs of 2019, the age-adjusted death rate from heart disease was 165.0[3] per 100,000 in Black women

Key Heart Disease In Black Women Fact

- Heart disease affects 47.3%[1] of Black women.

- Black women have the highest rates[1] of hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and stroke of any ethnicity in U.S. women.

- Black women are 50%[3] more likely to have high blood pressure as compared to White women.

- Black women had 2.4[2] times the risk of developing heart disease than White women.

- As of 2019, the age-adjusted death rate from heart disease was 165.0[3]ơ per 100,000 in Black women

Heart Disease In Black Women Statistics

Death Rate

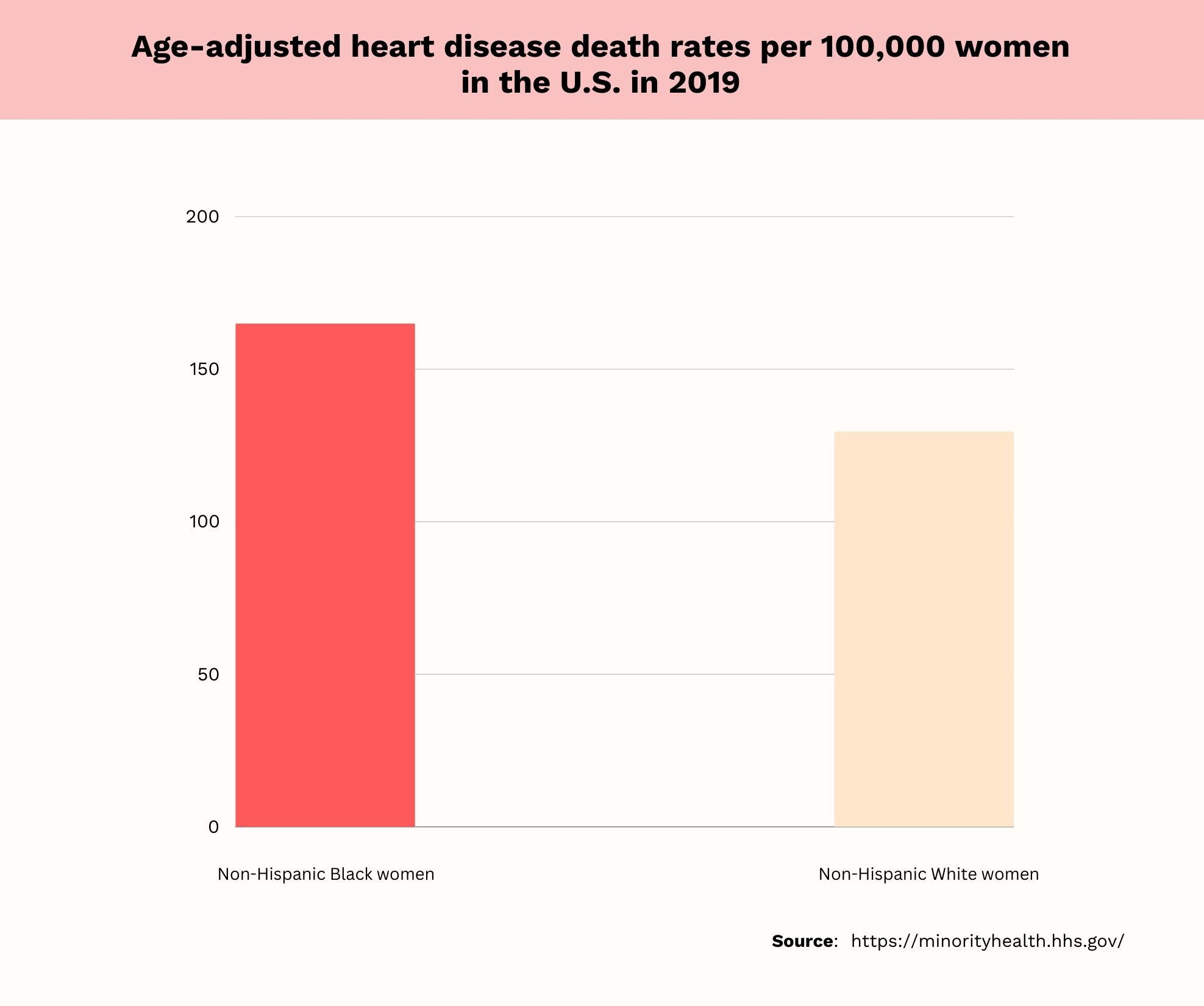

- In 2019, the heart disease death rate was 165.0[3] per 100,000 African American women.

- For Whites, the death rate was lower, at 129.6[3] per 100,000 women.

Statistics related to heart disease in African American women show higher death rates[3] in Black women compared to Whites. This is not surprising, given that coronary artery disease, which restricts blood flow to the heart, is more common in Black women. Among Black women, 5.2%[4] have coronary artery disease, compared to 3.2%[4] of their White counterparts.

Risk Factors

High Blood Pressure

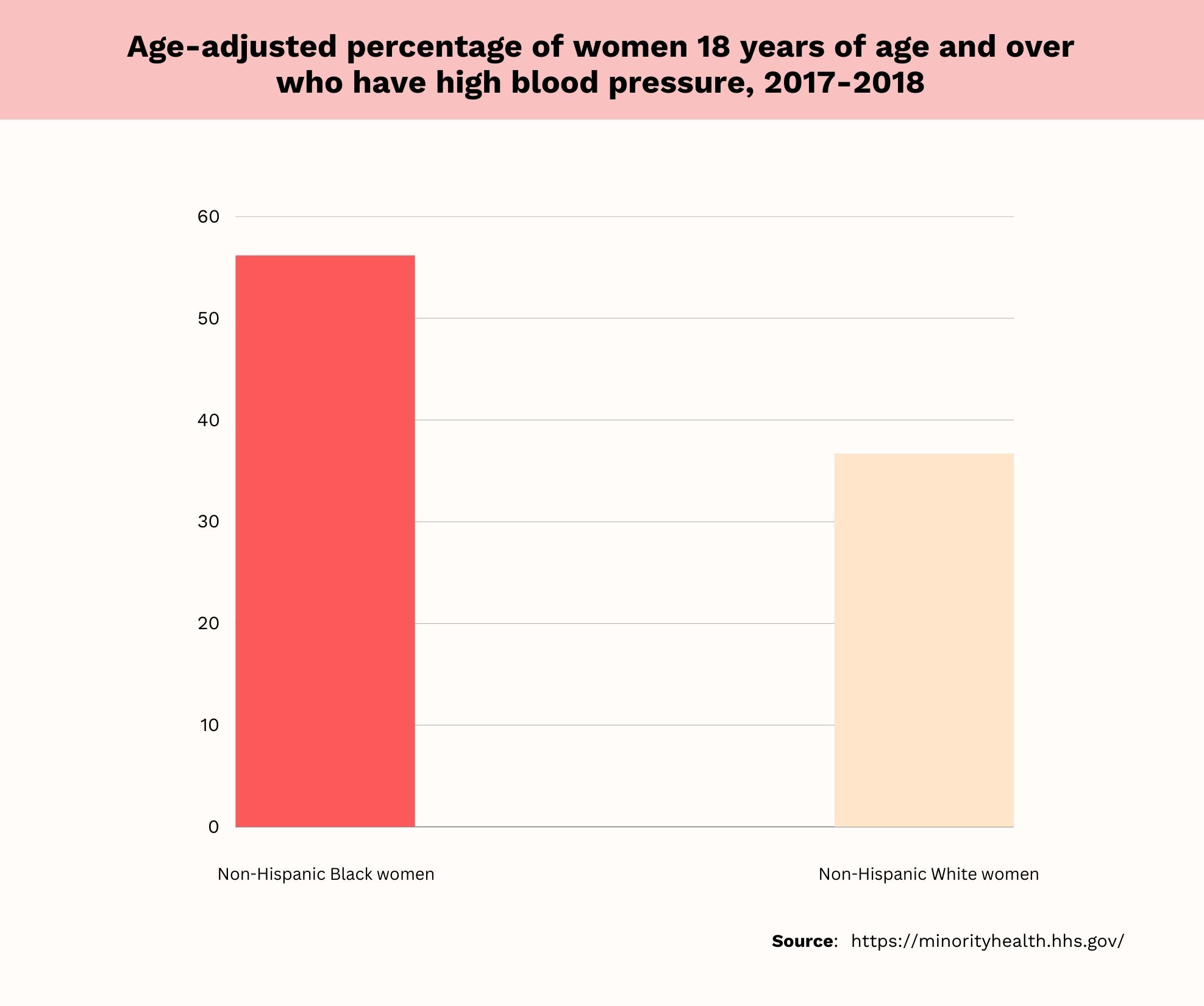

- In African American women, 56.7%[3] have high blood pressure.

- Among White females, 36.7%[3] have high blood pressure.

Many African American women have high blood pressure or hypertension.[3] The rate of hypertension is lower in White compared to African American women. Overall, the rate of hypertension is 1.5 times[3] higher among Black women compared to Whites.

Heart Disease In Black Women Facts To Know

Blacks Show Increased Aging In The Cardiovascular System

African American heart disease can be a result of faster aging of the cardiovascular system. One study looked at excess heart age[5] among different races. Excess heart age is the difference between a person’s chronological age and the age of their heart.

Cardiovascular disease risk factors lead to excess heart age. According to study results, non-Hispanic Blacks have an excess heart age of 13 years,[5] on average. Excess heart age averages 10.5 years[5] in Mexican Americans and 8.5 years[5] in non-Hispanic Whites.

An increase of 10 years in excess heart age increases the risk of death from heart disease by 65%.[5]

Heart Disease Trends Reflect Larger Health Disparities

Black women are more likely[3] than White women to die from coronary heart disease. Unfortunately, this fact is part of a much larger problem: health disparities between Blacks and Whites.

Black women aren’t just more likely to die from heart disease. They are at higher risk of death from any cause. The age-adjusted mortality rate for Black women is 802 per 100,000,[6] compared to 664 per 100,000[6] for White women.

Development Of High Blood Pressure Is More Common In Black Women Compared To Whites

Statistics on heart disease by age show that African American women are more likely than Whites to develop high blood pressure. Between the ages of 18 and 55, the incidence of high blood pressure is 75.7%[7] among Black women. In Whites, the incidence in this age range is 40.0%.[7]

In Black men, the incidence of high blood pressure from ages 18 to 55 is 75.5%.[7] For White men, the incidence is 54.5%.[7] Black women have a higher incidence of high blood pressure than White men and women. Black women’s incidence of high blood pressure is comparable to that of Black men.

Blacks Have Heart Attacks Earlier In Life

The heart attack age range may be slightly younger in Blacks compared to Whites. One study found the average age of those experiencing a heart attack was 72.0[8] for Blacks. This was compared to 74.0[8] years of age for Whites.

There is limited research evaluating the age of heart attack for African American women specifically. However, among Blacks, more heart attack victims are women compared to men. In the study above, 55.3%[8] of Black heart attack victims were women, compared to 44.7%[8] who were men.

Symptoms Of Heart Disease In Women

It’s important for women to be aware of their unique heart disease symptoms, which may vary from men’s symptoms. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,[9] the following can indicate heart disease in women:

- Pain or aching in the chest, called angina.

- Jaw, throat, or neck pain.

- Pain in the back or upper stomach.

- Excessive tiredness.

- Nausea or vomiting.

In some cases, women may not experience heart disease symptoms until they have a heart attack, which is an emergency. Heart attack symptoms[9] include extreme fatigue and discomfort or pain in the chest. Pain may also occur in the upper back or neck, and women may experience swelling, nausea, vomiting, and indigestion.

How To Prevent Heart Disease

The best way to promote heart health is to reduce heart disease risk factors. Below are specific risk factors and methods for reducing them. Many of these will also help you reach a healthy weight, further decreasing risk.

Reduce High Blood Pressure

One of the top risk factors for heart disease in African American women is hypertension. Remember, Black women are almost 60%[9] more likely than Whites to have high blood pressure.

African American women need to find ways to manage blood pressure to reduce heart disease risk. Lifestyle modifications, including diet, exercise, compliance with medication regimen, and stress management,[10] are beneficial.

Clinical trials show the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension[11] or DASH diet is beneficial for alleviating hypertension. This diet is rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy while limiting sodium, total and saturated fat, and cholesterol. Research with African American women has also shown that walking[12] three times per week for 45 minutes can alleviate hypertension.

It is also important for those with elevated blood pressure to be compliant with medications. Unfortunately, 84%[10] of Black women are non-adherent with taking medications to reduce blood pressure. Poor blood pressure control[13] is among the major risk factors for cardiovascular disease deaths.

Eliminate Substance Use

Cigarette smoking[9] and excessive drinking are behavioral risk factors for heart problems. If you smoke, completing a smoking cessation program can help you to give up cigarettes. This, in turn, will reduce the risk of developing heart disease.

If you drink, it’s important to keep drinking to a moderate level. For women, this means no more than one drink per day[14] on days you drink.

Lower Cholesterol Levels

Elevated blood cholesterol[9] increases heart disease risk in women. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol is particularly damaging.

Following a healthy diet is beneficial for reducing cholesterol levels.[15] Such a diet is low in saturated and trans fats and higher in fiber.

You can also reduce cholesterol levels by maintaining a healthy weight and exercising regularly.

Become Physical Active

Physical inactivity is a heart disease risk factor. The good news is that exercise can decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease,[16] independently of other risk factors.

Thirty minutes[16] of moderate-intensity exercise five times a week can reduce heart disease risk in African American adults. Moderate-intensity exercise[17] is defined as that which brings your heart rate to 64%-76% of its maximum. Max heart rate is calculated by subtracting your age from 220.

Manage Stress

Chronic stress can increase the risk of heart disease. Over the long term, stress has a negative impact on metabolic health. This can lead to the buildup of plaque in the arteries.

Reducing stress can therefore play a central role in improving heart health. Unfortunately, structural racism can create additional stress for African American adults. Racism[18] is also a leading contributor to health disparities, according to the American Heart Association’s scientific statement.

It is, therefore, critical that women of color take steps to reduce chronic stress. This can include seeking social support, practicing self-care, and setting goals related to stress management.[19]

When To See A Doctor

It’s important to see a doctor for regular checkups to monitor your heart health. A doctor can complete blood work to evaluate your blood pressure and blood cholesterol levels.

Beyond regular checkups, it’s imperative to seek medical care if you have heart disease symptoms, such as chest pain, excessive tiredness, nausea, vomiting, or jaw pain. A doctor can evaluate symptoms and provide medical intervention to promote health and well-being.

Conclusion

Women’s health data show that African American women are at increased risk of heart disease compared to other demographic groups. Lifestyle changes, including diet and exercise, can reduce the risk. However, health care providers and public health experts must also work to promote health equity for Black women.

Frequently Asked Questions

African Americans experience health disparities[3] that increase their risk for negative health outcomes. They are more likely than Whites to have high blood pressure,[7] which is a leading cause of heart disease.

Research shows that heart disease[20] is the leading cause of death in Black women. Heart disease deaths exceed deaths from cancer for Black women.

Normal blood pressure is under 120/80[21] and is not different for Blacks vs. Whites.

Evidence Based

Evidence Based